Historian Sigita GASPARAVICIENE

”Vilnius is a miracle of creation of nature and human hands, a harmonious combination of nature and civilisation that marvellously retained the balance of these two beginnings, which was the result of a wise understanding that nature for the human being is both a home and a shrine. The beauty of Vilnius was first shaped by rivers Neris and Vilnele and the woods, and only then by a nature-loving human being."

V. Drema. ”Vilnius Gone" Vilnius. 1991, p.340

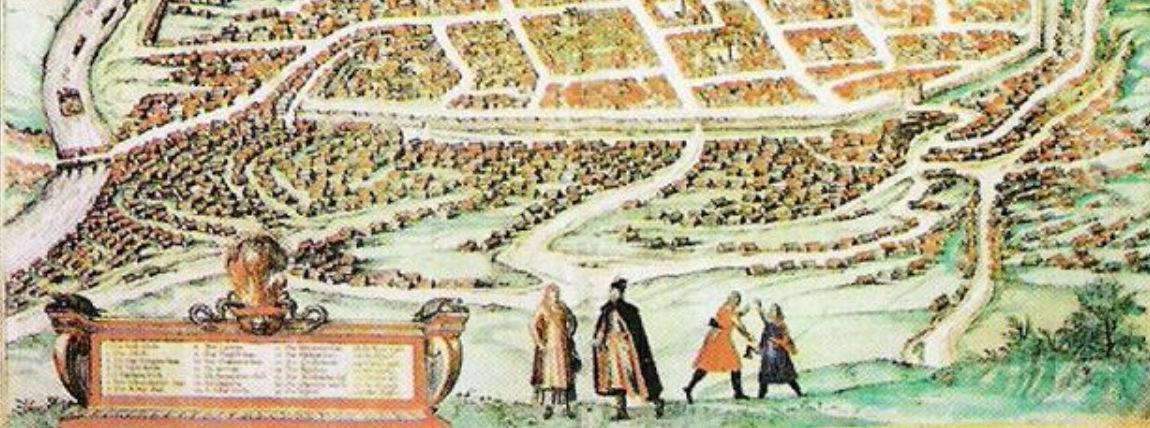

Nature conditioned the process of merging the city and the hills, rivers, river valleys and abundant vegetation that surrounded it in the early stages of the city development. Today we hold this close connection with nature as an important criterion of urban quality. The search for balance between elements of the city and nature began when the city had already been set up. In the 18th century this search in the shape of theoretical speculations had more to do with Vilnius Old Town, its buffer zone and partly Vilnius central area and separate residences. It was only since the beginning of the 19th century that the idea of development of natural inserts – vegetation system – included areas beyond the developed city area at the time.

The earliest green spaces of communal designation in Vilnius were oak groves. They are thought to have been growing in the territory of the present Museum of Applied Arts by River Vilnia, areas of Tilto, L.Stuokos- Gucevičiaus, Šventaragio, Sodu, and St.Stephen streets, the territory of the Sapiega Palace in Antakalnis district, etc.

Some time later recreational green spaces such as hunting and tournament grounds began to appear. 15th century historical sources mention cherry and other fruit tree gardens that Lithuanians cam to like, and notes on parks appear since the 16th century.

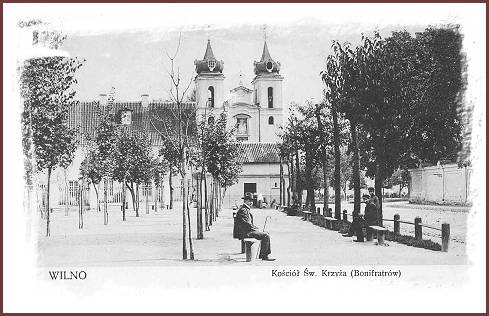

The system of Vilnius green spaces is comprised of an especially complex and abundant landscape, even more enriched by parks that had been fostered for a few hundred years. Verbal mythology associates some parks with the relicts of former sacred pagan groves. In the middle ages the city herself was dominated by the principles of shaping enclosed spaces predetermined by city architecture of defence character. Spaces providing useful produce – fruit, vegetables and herbs – were cultivated by monasteries located in the city outskirts. Functional power of green spaces was much supported by the grand dukes of the Grand Lithuanian Principality, especially by Žygimantas Augustas, during the rule of whom beautiful renaissance garden-parks were set up in Vilnius Lower Palace and Viršupis – the upper reaches of the river – roundabout the old trolley-bus terminal in Antakalnis. Green spaces became an obligatory part of palace ensembles in the Renaissance city and suburban residences. The oldest Vilnius green spaces include the garden of Vilnius bishops first mentioned as early as 1387, the garden of noblemen Goštautai – today’s L.Stuokos -Gucevičiaus street, in the territory of the Bonifratres monastery, today’s garden of the Sapiegos palace in Antakalnis.

There also were wonderful Radvilos gardens with ponds in the land plots of T.Vrublevskio-Tilto streets, private gardens of Bernadine (Fratres franciscan observantes), Jesuit and Carmelite monasteries. Geometrically shaped parks with concentrical alleys with fountains, ponds, flowerbeds of intricate shapes and mazes of clipped box-trees were the fashion of the 17-18th centuries. These were the so called Italian gardens the most beautiful of which are thought to have been in the residence of Vilnius Bishops, the then Sapiega Palace in Antakalnis, Sluhka palace on River Neris bank in today’s T.Kosciuškos street and Jesuit summer residence in Vingis, the river bend. The 18th century brings to fashion garden-parks of free landscape layout – the so called English gardens. Their spirit and expression were more in line with the Lithuanian understanding of nature, ideas of sentimentalism, and especially of romanticism of the early 19th c. supported by the nostalgia of the lost Lithuanian state. The work of J.Strumila (Strumillo), Vilnius gardener of the 1st half of the 19th c., and the project “Northern Gardens” that received much popularity in both Lithuania and Western Europe played in this a role of special significance. However, until the end of the 18th c. green spaces were mainly fostered in residences of Vilnius noblemen and gentry and monasteries and their management was mostly influenced by the general development of Western European green spaces. Public city green spaces received more attention only as late as the end of the 18th c. when Lithuania became part of the Russian Czar Empire and Vilnius - the province centre.

The trend of including green spaces into the city structure was very prominent in Vilnius city plans starting from the plan of Western part of Vilnius developed by L.Stuoka-Gucevičius in 1790 to Vilnius development plan of 1938. The end of the 18th c. saw the start of planting trees –poplars, lime trees and chestnut trees – along the main city streets. Development of green spaces architecture was greatly influenced by Vilnius University Botanical Gardens set up by University professors German G.Forster and French J.E.Gilbert in the courtyard of today’s building at 22 Pilies street. in 1782. The garden was some time later moved to Sereikiškes where it functioned until 1841 and was expanded, pampered and turned into the botanical science grounds at the initiative and due to huge devotion of our famous botanist Vilnius University professor S.B.Jundzilas (Jundzill). Fostering of city green spaces owes a lot to Vilnius gardeners S.Keppe, Weber and Weller’ gardening dynasties as well as Vilnius gardens’ commission set up in 1884.

The milestones for preservation of of the mass of green spaces and its introduction into the city urban structure were Vilnius development plans of 1817 and 1837. Later city plans also tried to develop this idea. It was due to them that the former political and cultural centre of the Grand Lithuanian Principality - territories of the Higher and Lower palaces, i.e. green spaces of the Castle hill and its foot the Botanical and Bernardine gardens – became the main nucleus of the city green spaces. Attempts were made to gradually extend it along River Vilnia through including into this system gardens of the Missionary Monastery and their ponds, and incorporating palace gardens of the territory of Subačiaus street into the Rasos suburban park and garden complex. In Antakalnis large green spaces were made of the former Pacai park by St. Peter and Paul’s church and parks of Latheran Canons’ Monastery, former Sapiega Palace and Trinitors’ Monastery. According to City development plans they had to be connected by boulevards with the nucleus of city green spaces –the Castle Hill and its surroundings. The 18-20th c. significant city green spaces were Žverynas and Vingis pinewood. Žverynas, owned by noblemen Radvilos until the 18th c., was the raising and hunting grounds for wild animals. When in the early 19th c. these grounds went to dukes Witgenstein, the area became a district of Vilnius suburban residencies. The first public city park started by Bishop I.J.Masalskis (Massalski) in Vingis pinewood in the end of the 18th c became the largest and most frequented by citizens city park by the end of the 19th c.

City green space development and management was much contributed to by the Gardens commission set up in 1884 at the effort of which Vilnius became one of the best managed Eastern European city with most tastefully developed green spaces. Their first job was the redevelopment of the nucleus of city green spaces – the Castle Hill and its surroundings –though connecting and newly planting the Botanical, Bernadines, Pushkin as well as the Cathedral squares following the example of Pinzo hill of the late 19th c. Rome through. It was followed by such new developments as St. George’s square (today’s Municipality Square), the square in front of the Franciscan Church in Traku street, squares at St. Catherine Church and Bonifratres Church and redevelopment and planting of the Town Hall Square, etc.

In 1938 city public green spaces, parks, squares, boulevards and street vegetation covered 1062.15 ha, while green spaces used for forestry, horticulture and plots for single-family houses covered 5769.18 ha, which added up to 6831.33 ha and comprised 65.68 % of the total city area.

The Official City Plan of 1938 continued to shape and improve the system of city green spaces. The major inlets of green spaces into the city were planned by River Neris from Turniškes at Valakupiai, in Antakalnis from Kalnu Park to the hill of Gediminas’ grave, and from Žverynas and Vingio Park through today’s Gedimino Avenue and in other directions. Sections of green spaces were planned to be taken further into the inner city alongside rivers, hills, boulevards and parks. These wedges of green spaces were planned to be connected with similar sections surrounding the city in a series of concentric rings, and dividing separate districts from one another. The system of Old Town green spaces was developed on the edges of the Old Town and retained the traditional shape of a wedge from the North to the South and from the West to the East until as late as the 2nd World War, which was done in an attempt to counterbalance the densely developed Old Town blocks.

The Castle Hill, green spaces at its foot and Kalnu (Hills) Park remained the main open space of the Old Town and component of its natural surrounding. A component of special value in the Official City Plan of 1938 was in its solution of the layout of the Higher (Naujamiestis) and Lower (Senamiestis) terrace. It attempted to retain the green massif of slopes separating them, with especially prominent green spaces planned in the area of K.Čiurlionio-K.Kalinausko streets. In 1945 authors of the new Vilnius official plan solved the problem of green spaces in a similar manner. However, ideas of 1938-1943 official plans were only put in reality in Cathedral Square, Daukanto- today’s Municipality – square, at Akmenu street and in other minor fragments.

The old Vilnius green spaces are not just natural, but also cultural monuments, both a sort of ecological history and a gift to us.